In 2020, PGE’s coal-fired power plant in Boardman, Oregon—the state’s largest emitter of greenhouse gases—is going offline. Naturally, there is much hype about how seriously this means we’re taking our climate responsibility, and the new clean tech future that is surely shining just beyond the horizon. There’s less fanfare about the fact that PGE intends to replace generating capacity with the new Carty gas plants, one already built and two still being permitted.

State agencies responsible for keeping Oregon’s proportional climate impact within survivable levels are using flawed methodologies that don’t account for fracked gas’s potential to leak raw methane into the atmosphere. However, even by the state’s own reckoning, these new power plants lock Oregon into emissions above the threshold for catastrophe.

Oregon has a climate mandate as a result of legislation passed last decade: reduce emissions to at least 75% below 1990 levels by 2050. (1) So it isn’t like living in Oklahoma, or dealing with the federal government where climate denial and active policy interventions on behalf of fossil fuel corporations prevail. Oregon’s approach is one of sober acknowledgement that climate change is the greatest threat of our time combined with quiet acquiescence to the fossil fuel industry just the same.

The state is reducing emissions on paper while locking us into catastrophe at Boardman. Understanding how this happens is useful for understanding the abject failure of institutional politics to address climate in general, and for conceiving strategies going forward.

The legislation which mandates the state’s emissions targets isn’t specific at all about how it is achieved. This is always the first step of institutional climate “progress”: make sweeping declarations about decarbonization and saving the future, then delegate the details to a commission or technical committee no one is paying attention to. This way, the promises can die in obscurity.

Here, the particular obscurity in which our climate promises die is called the Oregon Global Warming Commission. The commission is tasked with synthesizing information about different types of emissions and coordinating reduction efforts among different state agencies and the legislature.

There’s lots of divisions of labor. The Oregon Department of Transportation comes up with a strategy for reducing emissions from vehicles on the roads. The Oregon Public Utilities Commission and Energy Trust of Oregon have roles in energy efficiency measures which help meet CO2 targets. At every step of the way, there’s also a need for new legislation to give agencies the power to take the steps they identify as necessary. The OGWC is supposed to provide the systemic oversight to guide all the complex work happening simultaneously to reduce emissions from different sources. They write a report to the Oregon legislature every two years. To the extent that Oregon could be said to have a climate plan, the OGWC is its author. (2)

The OGWC is chaired by the president of a corporate sustainability consulting firm. Two of its ten voting positions are occupied by representatives of very polite environmental NGOs, the Oregon Environmental Council and the Nature Conservancy. There’s the owner of a vineyard. There’s an engineer and a Eugene city councilor/energy consultant. Then there’s the for-profit major emitters: the president and chief operating officer of Northwest Natural Gas, the Oregon Corporate Affairs Manager for Intel. There’s the Executive Director of the Port of Portland. One voting seat is empty.

Oh, and there’s the CEO of Portland General Electric, Jim Piro. He’s also one of the nine people currently tasked with coordinating the state’s climate efforts and making the recommendations that are supposed to ultimately become policy. We’re asking for a climate plan from the corporations responsible for the emissions the plan is supposed to address. It’s a particularly boring game of “what could possibly go wrong?” in which there are too many obvious answers.

The people who are breaking the world don’t know how to fix it. Even on paper, the OGWC can’t conceive of a strategy for meeting mandated emissions reductions. Even on paper warrants italicization because Oregon is reducing emissions an awful lot on paper, while on a trajectory of escalating emissions in, well, the corporeal world.

We met our earliest legislated emissions target (“arrest the growth of emissions by 2010”) because of the 2008 financial crisis. Naturally, there was some fanfare about how we were on a path to a green future that minimized the fact that our particular path—a reduction in overall economic activity—was inadvertent and actively resisted. (3)

As of their most recent (2015) report, the OGWC has made a set of extremely general policy recommendations. They’ve modeled the effects of these policies to the year 2050. It forecasts significant declines in CO2 emissions, but the forecasts require things like:

- Technologies that don’t yet exist

- Policies on the part of the federal government that were always far from certain and are extremely dubious at the particular moment

- Effects of market manipulations which have extensive histories of failure

- Carbon to simply disappear as it is juggled between different planning documents addressing different parts of the economy

OGWC describes its imaginary victories in a complex web of planning documents too numerous and tedious for virtually any non-specialist to pay attention to. In the future, we’ll plug our as-yet-uninvented smart appliances into our as-yet-unconstructed smart grid—poof!—there goes a few more million metric tons of CO2. Here’s our carbon pricing model—in a blinding flash emissions disappear. Insert graph showing our progress toward a prosperous future.

The absurdity reaches its torturous paramount in the climate plans that just shuffle the carbon to some other part of the economy where no one has a means of dealing with it. The state’s transportation strategy is heavily reliant on future cars which are powered by the grid, a plan that of course only reduces emissions if the grid isn’t heavily fossil fuel powered. But no one—not the OGWC or anyone else—is pursuing a strategy for that. Oregon’s Statewide Transportation Strategy is a document that simply moves carbon out of the transportation sector and into an imaginary realm. (4)

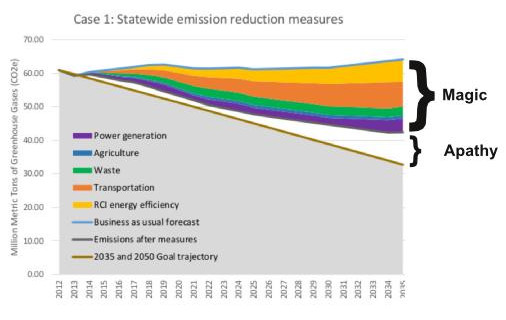

It is thus remarkable, when one considers the extent of wand waving involved in Oregon’s climate progress, that the OGWC can’t even meet our emissions mandate on paper. The graph below illustrates the situation visually, in which we see the relative role magic and apathy play in this approach.

It’s a path to a world of burning forests and dying seas, a world of famine and mass migration—but with lots of cool infographics, sustainability language, and technical committees.

Now that the financial crisis is over, emissions are steadily rising above our targets and forecast to continue doing so, until by 2050 we will be many millions of metric tons of CO2 beyond our state threshold. (5) Because power consumption contributes about 1/3 of Oregon’s GHG emissions, and because other emissions strategies (particularly transportation) are contingent on power decarbonization, there is absolutely no meaningful conversation to be had about climate action without getting the grid off of fossil fuels.

Significant but still woefully inadequate measures have been taken by the state legislature and the federal government. The federal Clean Power Plan was never implemented and is now being undone by a reality television star. Oregon’s Clean Energy and Coal Transition Plan, Senate Bill 1547, mandates the phasing out of coal from Oregon’s energy mix—whether burned in-state or purchased from more distant power plants—by 2035. It requires Oregon utilities to generate 50% of their power from renewables by 2040.

Ultimately, however, these measures put us nowhere we want to be—and PGE has built one new gas-fired power plant at Carty, and wants to construct two more, to make this failure of vision final.

What’s so appalling about this is that the company has access to the renewable energy that would meet its customers’ forecasted needs. Every few years PGE is required to issue an Integrated Resource Plan, a document that projects demand for electricity and identifies the resources it will use to meet it. These plans are then approved by the Oregon Public Utilities Commission.

Utilities don’t particularly like to talk about distributed renewable energy (like solar panels on people’s rooftops) because distributed energy threatens their profit. However, they will at least acknowledge the plausibility of big centralized solar and wind farms. PGE’s most recent IRP, from 2016, identifies three such resources: 103 megawatts of solar power in East Oregon, 338 mW in a Pacific Northwest wind farm, and 236 mW of wind power from Montana. (6) Combined, these resources total 677 mW of power. The Carty II gas-fired power plant—which PGE is currently getting the permits for from various Oregon state agencies—would produce 530 mW.

There is no technological or regulatory barrier to these wind and solar resources being used instead of building new fossil fuel infrastructure. The only barrier is greed. The company could use renewables instead of burning gas and make a profit, but they wouldn’t maximize profit.

Thus, PGE is simply choosing to burn the world, and no one in Oregon state government—not at the PUC, the legislature, or the OGWC (if the OGWC can plausibly be described as a separate entity from PGE)—seems to mind.

The tangled web of carbon and power briefly described here—in which people like Jim Piro move back and forth between climate-killing corporate CEO and state climate policy advisor, in which it is every agency’s hypothetical job to take climate action and thus no agency’s actual job to stop Carty—is invisible. It must be revealed. Making the unseen seen, forcing a response from institutional power and thus shifting the range of its possible behaviors, is a key premise of direct action.

This fight will be different than others in our region against new fossil fuel infrastructure, as it does not involve just bulk fossil fuel transport or an export market. It is a fight over how active power demand will be supplied and/or reduced. It is thus a critical nexus for engaging a broader set of questions concerning how we achieve radical reductions in emissions built in to our current ways of living. The range of scenarios conceivable to those in power are all predicated on the inherent need for continued economic expansion, and thus are inimical to life. They literally cannot envisage a shift away from their market logic even if the consequence for not doing so is the end of the world.

We can. We can envision far more aggressive reductions in power consumption when we don’t assume corporate profit is necessary, important, or particularly desirable. We can talk about the economic inequality in power consumption, where a wealthy minority consumes a hugely disproportionate amount of energy, while institutional discourse will always prefer to make us all equally liable for climate chaos. We can envision efforts at installing distributed renewable energy as earnest and aggressive as one would expect if everything depended on it.

PGE’s construction of the first Carty gas-fired plant in 2016, and the hasty permit approvals it is receiving for the second one, illustrate how completely meaningless broad aspirational climate laws, pacts, and proclamations without any implementing details are. The institutions have failed us completely on a matter central to the prospects for wellbeing and survival of people and the planet. We must articulate a vision beyond their scope, and we must pursue it outside the channels of their power.

- ORS 468A.205 section 1 tells us: “The Legislative Assembly declares that it is the policy of this state to reduce greenhouse gas emissions in Oregon . . .” and gives the emissions targets before summarily concluding: “This section does not create any additional regulatory authority for an agency of the executive department . . .” https://www.oregonlaws.org/ors/468A.205

- More specifically, if Oregon has a climate plan it’s a combination of the OGWC’s most recent biennial report to the legislature http://www.keeporegoncool.org/sites/default/files/ogwc-standard-documents/OGWC_Rpt_Leg_2015_final.pdf and the Roadmap to 2020 http://www.keeporegoncool.org/sites/default/files/Integrated_OGWC_Interim_Roadmap_to_2020_Oct29_11-19Additions.pdf One quickly finds, however, that embedded in these documents are details and assumptions from many other documents. A more detailed map of the interrelations between these different agency efforts will be in a future blog post.

- The tepid fanfare: “With these numbers we can report with continued confidence that Oregon likely did meet its first greenhouse gas reduction goal of arresting emissions growth and beginning to reduce emissions after 2010. This conclusion is a positive one, but we must temper it with a few possible caveats: 2009 and 2010 emissions were likely suppressed by continued effects of the recession . . .” (OGWC 2015 Report to Legislature p. 29)

- This post is intended to be the first of a series. The magical disappearing carbon act will be documented in far more painfully thorough detail shortly.

- The confession that follows the fanfare: “Now for the less positive news: despite an overall lower forecast than previously reported thanks to the implementation of Oregon’s RPS and other policies, that forecast is not expected to come within striking distance of our 2020 and 2050 emission reduction goals. Rather, with 5 years left to a go we appear to be on track to miss our 2020 goal by just over 11 million MTCO2e. That gap widens to 32 million MTCO2e in 2035 on a linear path to our 2050 goal.” (OGWC 2015 Report to Legislature p. 32)

- Portland General Electric 2016 Integrated Resource Plan (p. 212) https://www.portlandgeneral.com/-/media/public/our-company/energy-strategy/documents/2016-irp.pdf?la=en